There was a time when, if you wanted a great touring bike, you pretty much had to build it yourself. If you had a healthy budget and knew where to look, you could have a good frame built for you by somebody and select all the best parts for touring. Or you'd buy a bike off the showroom floor that came as close as you could get, and change out a bunch of parts to get it the rest of the way to where you wanted it.

When it came to the components for a good touring bike, you had to pick out the best parts from a variety of component makers, each with their own specialty. For a long time, most of them were French. For example, you'd select a triple T.A. Cyclotouriste crank, or perhaps the Stronglight 49 -- either way you'd have that 50.4 BCD, and a wide range of available chainring sizes, and a really small granny ring. For brakes, you'd get Mafac -- center pulls or maybe cantilevers. For the rear derailleur, probably a Huret -- the Duopar if you could get one. On the front, maybe a Simplex Super LJ. Hubs? Maxicar was a great choice. By 1980, less traditional touring cyclists might have substituted a Sugino crank or SunTour derailleurs.

It was a lot easier equipping a top-quality racing bike. If you wanted the best you only needed to know one name: Campagnolo. By the 1960s, Campy (or Campag for my readers in the U.K. or Australia) made pretty much everything needed for a bike, and once they introduced their own brakes in '68, the "full Campy" was born. You could get the whole Campy gruppo and the only other decisions left to make were for the stem and handlebars (most people went with Cinelli) and a saddle.

For tourists, there was no equivalent to the "gruppo." That is, until 1981. That was when Shimano introduced the "Deore Touring Ensemble."

![]() OK, I guess I'm overstating the "complete gruppo" notion a bit (and actually, I cringe when people use the word "gruppo" with anything other than Campagnolo). At first, the Deore line consisted of the crank and bottom bracket, pedals, front and rear derailleurs, and shift levers. Apparently by Shimano's rationale at the time, the remaining parts of the group, such as hubs, brakes, and headset, could be filled in with parts from the 600EX line which were finished to a similar quality. The 600 hubs could be had in traditional threaded freewheel (600) or cassette freehub (600EX) configurations. The 600EX brakes were available in a 57-mm reach side pull, which was probably considered adequate for touring by some at the time, though the 1982 Shimano catalog shows a pair of cantilever brakes designated as 600-level (apart from the catalog, I've never actually seen a pair!). Within a year or two, Deore cantilever brakes and hubs would be added to round out the group.

OK, I guess I'm overstating the "complete gruppo" notion a bit (and actually, I cringe when people use the word "gruppo" with anything other than Campagnolo). At first, the Deore line consisted of the crank and bottom bracket, pedals, front and rear derailleurs, and shift levers. Apparently by Shimano's rationale at the time, the remaining parts of the group, such as hubs, brakes, and headset, could be filled in with parts from the 600EX line which were finished to a similar quality. The 600 hubs could be had in traditional threaded freewheel (600) or cassette freehub (600EX) configurations. The 600EX brakes were available in a 57-mm reach side pull, which was probably considered adequate for touring by some at the time, though the 1982 Shimano catalog shows a pair of cantilever brakes designated as 600-level (apart from the catalog, I've never actually seen a pair!). Within a year or two, Deore cantilever brakes and hubs would be added to round out the group.

The French influence could readily be seen in the original Deore crankset. Like the standard-bearer of the time, the T.A. Cyclotouriste, the Deore's large ring bolted to a small 50.4 BCD spider, and the middle and inner rings mounted on to the big ring. However, the Deore's big ring looked thicker and less "flat" compared to the French counterparts. In Bicycling magazine's original 1982 review of the group (May 1982), they said that the large Deore chainring was more resistant to flexing than the T.A. version. By the mid 80s, however, Shimano would adopt the 110/74 BCD favored by Sugino, and that would become the new standard for wide range triple cranksets for a long time to come.

The Deore pedals were an unusual innovation that never really caught on. Called Dyna Drive in the typical Shimano fashion of inventing new names for everything, the design more or less eliminated the usual pedal axle by incorporating the bearings into a large-diameter threaded stub. The cranks had a corresponding large diameter threaded hole for the pedals (if someone wanted to use "normal" pedals with the Dyna Drive crank, Shimano made threaded insert adapters for the crank). The DD was also available on the Dura-Ace and 600 groups. The benefit was supposed to be that they would allow a lower pedal platform and place the bottom of the foot lower in relation to the pedaling axis. I don't really understand how that is supposed to lead to better biomechanics in the pedal stroke, but then I never really "got" Biopace chainrings, either. What I do know is that reviewers said the pedals offered a nice, wide, supportive platform, but also had a slightly wider "Q-factor" and were more likely to strike the pavement when cornering.

The Deore rear derailleur was like a beefed up 600EX, with medium and long cage options, and with some extra tweaks to make it better suited for heavy duty and long-distance touring use. It also came marketed with its fair share of Shimano-isms: "Servo-Panta,""Centeron,""Hatch-Plate," and "Sealed Mechanism." Here's a translation: Servo-Panta is Shimano-ese for dual-sprung pivots -- that is, both the top and bottom pivots on the derailleur were spring-loaded, Simplex-style. Centeron was Shimano's little trick of having some lateral play in the jockey pulley. Combined with the special Centeron shift levers which also had a bit of extra movement designed into them, and a little extra free play in the derailleur itself, the Deore rear derailleur would more or less "center" itself on the cogs when shifting, thereby making for smoother, quieter operation. Hatch-Plate meant that there was not a full back plate on the pulley cage -- only a small tab to keep the chain from accidentally coming off the pulleys. That tab, or "hatch plate," could be moved aside, allowing the chain to be installed or removed easily from the derailleur. Note that SunTour had a similar feature on its various GT models, except that it was the front of the pulley cage that was open instead of the back. The hatch plate also meant the cage could get closer to the spokes, making it easier to fit 6 cogs into 5-speed spacing. Sealed Mechanism is an easy one. The spring-loaded pivots were set to the proper spring tension at the factory, then sealed -- no adjustments or maintenance needed, which was good because I doubt it was possible. Though it would not shift quite as well as the slant-parallelograms from SunTour, it was a solid, durable derailleur.

There isn't a lot to say about the front derailleur other than that I don't think it would look totally out of place with a modern component group (No, I take that back -- it looks much better than a lot of the black-painted, garish-logo'd derailleurs of today). Front derailleurs haven't changed much in 30+ years, either in form or function. Reviewers found the Deore front shifter to work well for triple cranks -- at least as well if not better than the top competition of the day. Of course, it did still have its own Shimano-isms, in this case, the "Trap-Ease Mechanism" which meant that the derailleur angled up and out as it shifted up to the larger ring. It was supposed to improve those upshifts.

Ultimately, the "Deore Touring Ensemble" did not actually do for touring bicycles what Campagnolo did for racers -- not even close. Even though it was introduced at just the time when lots of Japanese bicycle manufacturers had figured out how to make really nice loaded-touring bikes, many of those were leaving the factories with a mix of SunTour (gears and derailleurs), Sugino, SR, or Takagi (cranks) and Dia Compe (brakes). In fact, I checked with friends on the Classic Rendezvous group, and we could only come up with two or three bikes that came with the full Deore group from the factory. Otherwise there were a few makers, such as Schwinn or Raleigh, who used the Deore derailleurs, but not the other components from the set. I'm sure the crank and Dyna Drive pedal combination were off-putting -- yet another example of Shimano gimmickry and not playing well with others.

No, the real impact of Deore turned out to be with the mountain bike market which would really take off soon after the group's release. Though SunTour got a slight jump on the MTB market, engineering problems with the first SunTour MounTech derailleurs gave Shimano a chance to catch up. The first re-styling of the Deore group included the "deer head" icon that seemed to hint at the shift in focus (to be honest, I can't say exactly why a deer head seems more mountain-bikey than touring -- but for some reason it does). Well, that, and the fact that they also came out with flat-bar brake levers and thumb shifters -- the writing was on the wall. Touring bikes were out. Mountain bikes were in.

Today, really good road touring bikes are a rarity -- and those that are available from the big mainstream manufacturers often have overly huge, tacky-looking mountain bike components: wide Q-factor MTB cranks, ungainly derailleurs, V-brakes. If someone wants a more classic, traditional touring bike today, they have to go the same route that that touring cyclists did "back in the day" -- get a frame set and select all the parts themselves from a variety of component manufacturers (and maybe hunt eBay for some classic pieces from the past). We've come so far, only to end up back in the same place.

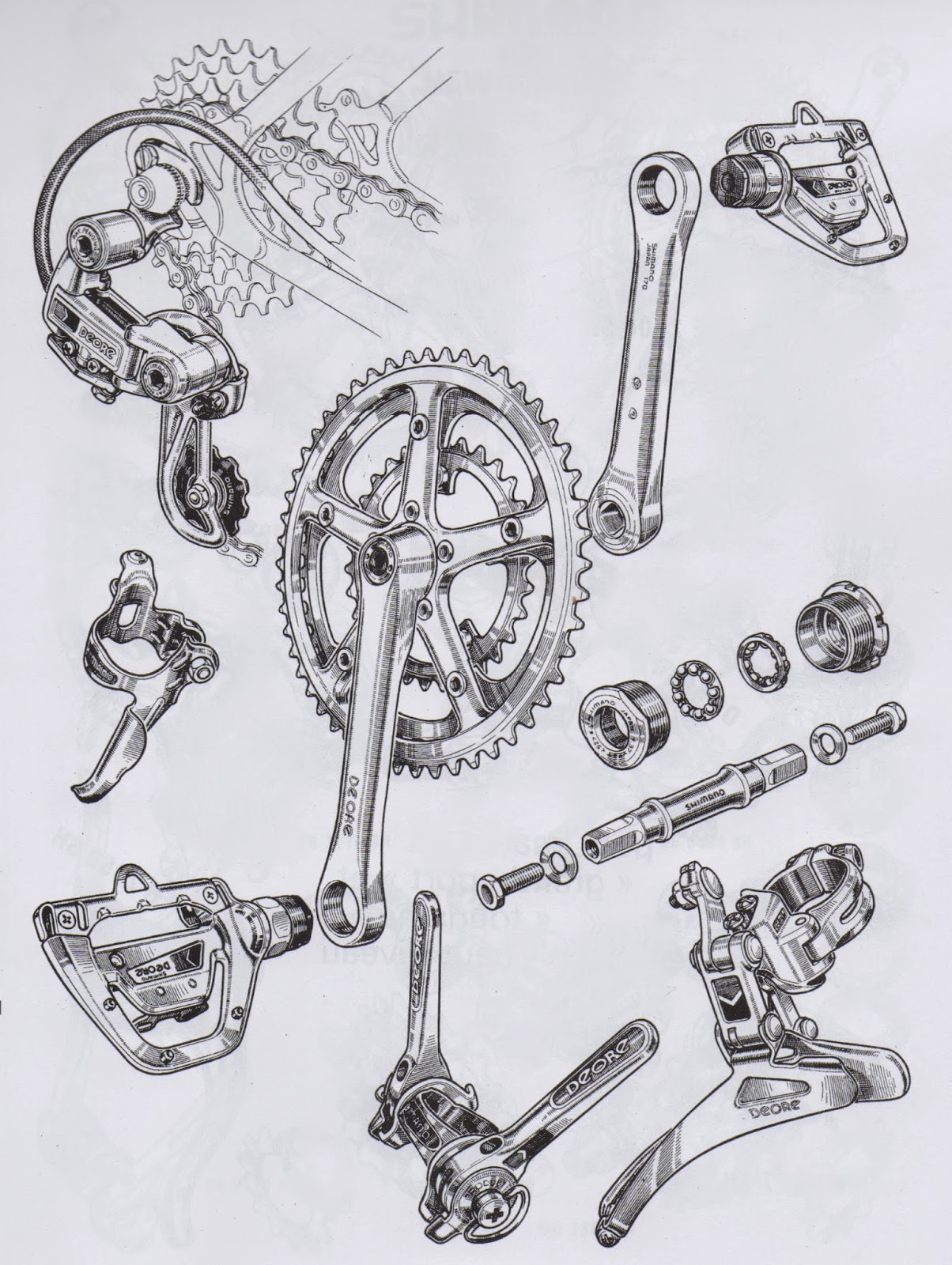

|

| A Daniel Rebour illustration of the first Deore "Touring Ensemble" (not gruppo). |

When it came to the components for a good touring bike, you had to pick out the best parts from a variety of component makers, each with their own specialty. For a long time, most of them were French. For example, you'd select a triple T.A. Cyclotouriste crank, or perhaps the Stronglight 49 -- either way you'd have that 50.4 BCD, and a wide range of available chainring sizes, and a really small granny ring. For brakes, you'd get Mafac -- center pulls or maybe cantilevers. For the rear derailleur, probably a Huret -- the Duopar if you could get one. On the front, maybe a Simplex Super LJ. Hubs? Maxicar was a great choice. By 1980, less traditional touring cyclists might have substituted a Sugino crank or SunTour derailleurs.

It was a lot easier equipping a top-quality racing bike. If you wanted the best you only needed to know one name: Campagnolo. By the 1960s, Campy (or Campag for my readers in the U.K. or Australia) made pretty much everything needed for a bike, and once they introduced their own brakes in '68, the "full Campy" was born. You could get the whole Campy gruppo and the only other decisions left to make were for the stem and handlebars (most people went with Cinelli) and a saddle.

For tourists, there was no equivalent to the "gruppo." That is, until 1981. That was when Shimano introduced the "Deore Touring Ensemble."

OK, I guess I'm overstating the "complete gruppo" notion a bit (and actually, I cringe when people use the word "gruppo" with anything other than Campagnolo). At first, the Deore line consisted of the crank and bottom bracket, pedals, front and rear derailleurs, and shift levers. Apparently by Shimano's rationale at the time, the remaining parts of the group, such as hubs, brakes, and headset, could be filled in with parts from the 600EX line which were finished to a similar quality. The 600 hubs could be had in traditional threaded freewheel (600) or cassette freehub (600EX) configurations. The 600EX brakes were available in a 57-mm reach side pull, which was probably considered adequate for touring by some at the time, though the 1982 Shimano catalog shows a pair of cantilever brakes designated as 600-level (apart from the catalog, I've never actually seen a pair!). Within a year or two, Deore cantilever brakes and hubs would be added to round out the group.

OK, I guess I'm overstating the "complete gruppo" notion a bit (and actually, I cringe when people use the word "gruppo" with anything other than Campagnolo). At first, the Deore line consisted of the crank and bottom bracket, pedals, front and rear derailleurs, and shift levers. Apparently by Shimano's rationale at the time, the remaining parts of the group, such as hubs, brakes, and headset, could be filled in with parts from the 600EX line which were finished to a similar quality. The 600 hubs could be had in traditional threaded freewheel (600) or cassette freehub (600EX) configurations. The 600EX brakes were available in a 57-mm reach side pull, which was probably considered adequate for touring by some at the time, though the 1982 Shimano catalog shows a pair of cantilever brakes designated as 600-level (apart from the catalog, I've never actually seen a pair!). Within a year or two, Deore cantilever brakes and hubs would be added to round out the group.The French influence could readily be seen in the original Deore crankset. Like the standard-bearer of the time, the T.A. Cyclotouriste, the Deore's large ring bolted to a small 50.4 BCD spider, and the middle and inner rings mounted on to the big ring. However, the Deore's big ring looked thicker and less "flat" compared to the French counterparts. In Bicycling magazine's original 1982 review of the group (May 1982), they said that the large Deore chainring was more resistant to flexing than the T.A. version. By the mid 80s, however, Shimano would adopt the 110/74 BCD favored by Sugino, and that would become the new standard for wide range triple cranksets for a long time to come.

The Deore pedals were an unusual innovation that never really caught on. Called Dyna Drive in the typical Shimano fashion of inventing new names for everything, the design more or less eliminated the usual pedal axle by incorporating the bearings into a large-diameter threaded stub. The cranks had a corresponding large diameter threaded hole for the pedals (if someone wanted to use "normal" pedals with the Dyna Drive crank, Shimano made threaded insert adapters for the crank). The DD was also available on the Dura-Ace and 600 groups. The benefit was supposed to be that they would allow a lower pedal platform and place the bottom of the foot lower in relation to the pedaling axis. I don't really understand how that is supposed to lead to better biomechanics in the pedal stroke, but then I never really "got" Biopace chainrings, either. What I do know is that reviewers said the pedals offered a nice, wide, supportive platform, but also had a slightly wider "Q-factor" and were more likely to strike the pavement when cornering.

The Deore rear derailleur was like a beefed up 600EX, with medium and long cage options, and with some extra tweaks to make it better suited for heavy duty and long-distance touring use. It also came marketed with its fair share of Shimano-isms: "Servo-Panta,""Centeron,""Hatch-Plate," and "Sealed Mechanism." Here's a translation: Servo-Panta is Shimano-ese for dual-sprung pivots -- that is, both the top and bottom pivots on the derailleur were spring-loaded, Simplex-style. Centeron was Shimano's little trick of having some lateral play in the jockey pulley. Combined with the special Centeron shift levers which also had a bit of extra movement designed into them, and a little extra free play in the derailleur itself, the Deore rear derailleur would more or less "center" itself on the cogs when shifting, thereby making for smoother, quieter operation. Hatch-Plate meant that there was not a full back plate on the pulley cage -- only a small tab to keep the chain from accidentally coming off the pulleys. That tab, or "hatch plate," could be moved aside, allowing the chain to be installed or removed easily from the derailleur. Note that SunTour had a similar feature on its various GT models, except that it was the front of the pulley cage that was open instead of the back. The hatch plate also meant the cage could get closer to the spokes, making it easier to fit 6 cogs into 5-speed spacing. Sealed Mechanism is an easy one. The spring-loaded pivots were set to the proper spring tension at the factory, then sealed -- no adjustments or maintenance needed, which was good because I doubt it was possible. Though it would not shift quite as well as the slant-parallelograms from SunTour, it was a solid, durable derailleur.

There isn't a lot to say about the front derailleur other than that I don't think it would look totally out of place with a modern component group (No, I take that back -- it looks much better than a lot of the black-painted, garish-logo'd derailleurs of today). Front derailleurs haven't changed much in 30+ years, either in form or function. Reviewers found the Deore front shifter to work well for triple cranks -- at least as well if not better than the top competition of the day. Of course, it did still have its own Shimano-isms, in this case, the "Trap-Ease Mechanism" which meant that the derailleur angled up and out as it shifted up to the larger ring. It was supposed to improve those upshifts.

| I don't know why the deer head icon seems more "mountain-bikey" than "touring-bikey" -- but it does. |

No, the real impact of Deore turned out to be with the mountain bike market which would really take off soon after the group's release. Though SunTour got a slight jump on the MTB market, engineering problems with the first SunTour MounTech derailleurs gave Shimano a chance to catch up. The first re-styling of the Deore group included the "deer head" icon that seemed to hint at the shift in focus (to be honest, I can't say exactly why a deer head seems more mountain-bikey than touring -- but for some reason it does). Well, that, and the fact that they also came out with flat-bar brake levers and thumb shifters -- the writing was on the wall. Touring bikes were out. Mountain bikes were in.

Today, really good road touring bikes are a rarity -- and those that are available from the big mainstream manufacturers often have overly huge, tacky-looking mountain bike components: wide Q-factor MTB cranks, ungainly derailleurs, V-brakes. If someone wants a more classic, traditional touring bike today, they have to go the same route that that touring cyclists did "back in the day" -- get a frame set and select all the parts themselves from a variety of component manufacturers (and maybe hunt eBay for some classic pieces from the past). We've come so far, only to end up back in the same place.