As the next installment of what I suppose has become a "series" on steel tubing used on classic bikes, I'll take some time to look at Japanese tubing manufacturers Tange and Ishiwata. Both companies made high-quality bicycle tubing that was in many ways the equal of European tubing giants Reynolds and Columbus -- although acceptance by the performance and high-end bicycle market (at least outside of Japan) took time.

Tange started out in 1920, originally producing bicycle forks, and expanding to butted tubing in the 1950s. By the 1970s, they had expanded to make all the frame components, including stays, dropouts and lugs. (Tange History)

Until the mid-80s Tange was probably best known for their mainstay tube sets, Champion #1 and #2 (later called simply #1 and #2) -- cold-worked, butted chrome-moly tubing that compared favorably to Columbus SL and SP tube sets. For instance, the down tube of Tange #1 was butted to .8/.5/.8 mm, while the #2 was .9/.6/.9 mm. These tube sets were used on a lot of higher end Japanese-built bikes being imported to the U.S. in the late 70s and early 80s. There were also thicker-walled, heavier sets, called #3, #4 and #5, available for loaded touring and other applications where more durability was required.

Tange also made a manganese molybdenum alloy, Mangaloy 2001, that should have compared pretty favorably to Reynolds 531, at least in terms of its basic characteristics, though it was heavier, (thicker walled than Reynolds) much less expensive, and generally found on lower-end models. In the early 80s, some lower priced Treks (such as the 400 series) were built with it.

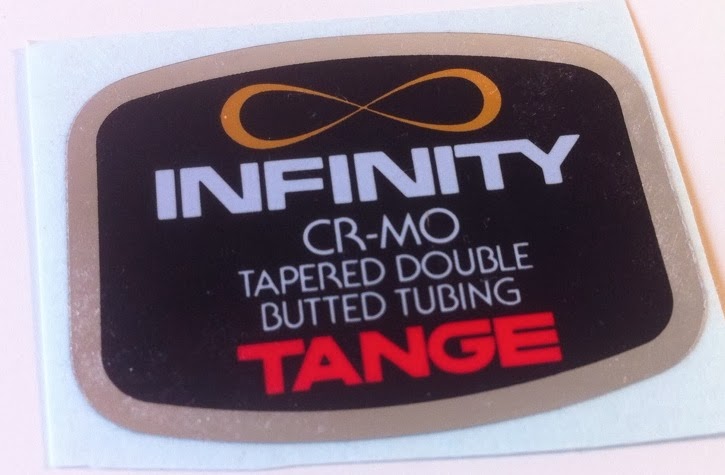

A cheaper tube set was created by Tange in the 80s: Infinity -- designed as a good quality but low-cost set for lower-priced bicycles. It was a seamed tubing, which meant that it started out as flat stock. It could be rolled out with different thicknesses along its length, then formed around a mandrel and welded into a tube. Additional working made the welded seam invisible. Many people would be turned off by the thought of seamed tubing, but in reality, there was not likely a big difference in strength. And the manufacturing method used meant that the butting could be customized without adding complexity or cost.

![]() In 1985, Tange hit the big time when they came up with their heat-treated Prestige tubing. Like Reynolds 753, but made from chrome-moly as opposed to manganese alloy, Prestige had the tensile strength to be drawn to super thin-walled dimensions -- only 0.4 mm in the center section with the regular version. A "Super Lite" version of Prestige was only 0.3 mm in the center section! Another advantage was that, unlike 753, no special certification was needed to use it, so Prestige gained much more acceptance among frame builders. Versions of Prestige are still used today.

In 1985, Tange hit the big time when they came up with their heat-treated Prestige tubing. Like Reynolds 753, but made from chrome-moly as opposed to manganese alloy, Prestige had the tensile strength to be drawn to super thin-walled dimensions -- only 0.4 mm in the center section with the regular version. A "Super Lite" version of Prestige was only 0.3 mm in the center section! Another advantage was that, unlike 753, no special certification was needed to use it, so Prestige gained much more acceptance among frame builders. Versions of Prestige are still used today.

I read an article by builder Dave Moulton about a bike he built with Prestige -- a one-of-a-kind bike because at that point in his career, Moulton's bikes were almost all built with Columbus. (Pictured on the left)

Another interesting note about Tange tubing is their relationship with Tom Ritchey. When Ritchey was looking for someone who could put into production some new ideas he had for butted tubing -- with specially tapered and directional-designed butted sections -- he first approached Columbus. Apparently, they were unable to manufacture it. He then went to Tange, who had recently started making their heat-treated Prestige, and they were able to make it work and manufacture it. Ritchey "Logic" tubing was the result. (Ritchey In His Own Words).

It is pretty difficult to find the history of Ishiwata tubing. The earliest mentions I can find of it are from the 1970s, but nothing very specific. In any case, their best tube sets through the 70s and 80s were seamless, double-butted chrome-moly, labeled "019" and "022." The late Sheldon Brown's website has some info about Ishiwata, most of which in turn came from Andrew Muzi of The Yellow Jersey bike shop in Madison, WI. (see sheldonbrown.com)

In material composition and in specification, Ishiwata 019 and 022 were (like Tange #1 and #2) very comparable to Columbus SL and SP. In fact, many people claim that the Ishiwata tubes were, at least in their surface finish quality, even nicer than the much more expensive Columbus tubes. For instance, in the early 80s, Tom Kellogg, probably best known today for his Spectrum Cycles, was working for Ross Bicycles developing their "Signature" line of hand-built bikes (something like their answer to Schwinn's Paramount line). Kellogg specified Ishiwata in those bikes. I found a quote that I couldn't verify, but Kellogg reportedly said of Ishiwata tubing, "It's like little men polished the inside."

The names "019" and "022" refer to the claimed weight of the tube set -- i.e., "019" (drawn to 0.8/0.5/0.8 mm) weighed 1.9 kilos, while "022" (drawn to 0.9/0.6/0.9 mm) weighed 2.2 kilos. Less well-known (and much rarer) are the "017" and "015" tube sets. Despite not being heat-treated, these tubes were drawn down to super-thin dimensions. The "017" was 0.7/0.4/0.7 mm, while the "015" was 0.6/0.4/0.6 -- with the down tube even thinner (0.35 mm!) in the center section! Needless to say, these were only used for track or time trial bikes, and likely only for very lightweight riders.

Ishiwata also produced triple-butted and quad-butted chrome-moly tubing, known as EX and EXO respectively. It is not unusual to find decent-quality Japanese-built bikes with those tube sets. In the 1980s, they were apparently even producing carbon-fiber tubing (in their catalog they were calling it CFRP - or carbon fiber reinforced plastic) and aluminum lugs to join the tubes. (see the catalogs at Equus Bicycle Info)

Tange started out in 1920, originally producing bicycle forks, and expanding to butted tubing in the 1950s. By the 1970s, they had expanded to make all the frame components, including stays, dropouts and lugs. (Tange History)

Until the mid-80s Tange was probably best known for their mainstay tube sets, Champion #1 and #2 (later called simply #1 and #2) -- cold-worked, butted chrome-moly tubing that compared favorably to Columbus SL and SP tube sets. For instance, the down tube of Tange #1 was butted to .8/.5/.8 mm, while the #2 was .9/.6/.9 mm. These tube sets were used on a lot of higher end Japanese-built bikes being imported to the U.S. in the late 70s and early 80s. There were also thicker-walled, heavier sets, called #3, #4 and #5, available for loaded touring and other applications where more durability was required.

Tange also made a manganese molybdenum alloy, Mangaloy 2001, that should have compared pretty favorably to Reynolds 531, at least in terms of its basic characteristics, though it was heavier, (thicker walled than Reynolds) much less expensive, and generally found on lower-end models. In the early 80s, some lower priced Treks (such as the 400 series) were built with it.

A cheaper tube set was created by Tange in the 80s: Infinity -- designed as a good quality but low-cost set for lower-priced bicycles. It was a seamed tubing, which meant that it started out as flat stock. It could be rolled out with different thicknesses along its length, then formed around a mandrel and welded into a tube. Additional working made the welded seam invisible. Many people would be turned off by the thought of seamed tubing, but in reality, there was not likely a big difference in strength. And the manufacturing method used meant that the butting could be customized without adding complexity or cost.

In 1985, Tange hit the big time when they came up with their heat-treated Prestige tubing. Like Reynolds 753, but made from chrome-moly as opposed to manganese alloy, Prestige had the tensile strength to be drawn to super thin-walled dimensions -- only 0.4 mm in the center section with the regular version. A "Super Lite" version of Prestige was only 0.3 mm in the center section! Another advantage was that, unlike 753, no special certification was needed to use it, so Prestige gained much more acceptance among frame builders. Versions of Prestige are still used today.

In 1985, Tange hit the big time when they came up with their heat-treated Prestige tubing. Like Reynolds 753, but made from chrome-moly as opposed to manganese alloy, Prestige had the tensile strength to be drawn to super thin-walled dimensions -- only 0.4 mm in the center section with the regular version. A "Super Lite" version of Prestige was only 0.3 mm in the center section! Another advantage was that, unlike 753, no special certification was needed to use it, so Prestige gained much more acceptance among frame builders. Versions of Prestige are still used today.I read an article by builder Dave Moulton about a bike he built with Prestige -- a one-of-a-kind bike because at that point in his career, Moulton's bikes were almost all built with Columbus. (Pictured on the left)

Another interesting note about Tange tubing is their relationship with Tom Ritchey. When Ritchey was looking for someone who could put into production some new ideas he had for butted tubing -- with specially tapered and directional-designed butted sections -- he first approached Columbus. Apparently, they were unable to manufacture it. He then went to Tange, who had recently started making their heat-treated Prestige, and they were able to make it work and manufacture it. Ritchey "Logic" tubing was the result. (Ritchey In His Own Words).

It is pretty difficult to find the history of Ishiwata tubing. The earliest mentions I can find of it are from the 1970s, but nothing very specific. In any case, their best tube sets through the 70s and 80s were seamless, double-butted chrome-moly, labeled "019" and "022." The late Sheldon Brown's website has some info about Ishiwata, most of which in turn came from Andrew Muzi of The Yellow Jersey bike shop in Madison, WI. (see sheldonbrown.com)

|

| Early 80s catalog scan from the Equus Bicycle Info Project |

Ishiwata also produced triple-butted and quad-butted chrome-moly tubing, known as EX and EXO respectively. It is not unusual to find decent-quality Japanese-built bikes with those tube sets. In the 1980s, they were apparently even producing carbon-fiber tubing (in their catalog they were calling it CFRP - or carbon fiber reinforced plastic) and aluminum lugs to join the tubes. (see the catalogs at Equus Bicycle Info)

|

| Look closely at that unique little tubing sticker on 3Rensho frames and you'll see the Ishiwata name. |

Of course, many Japanese manufacturers used Ishiwata tubing (sometimes labeled under other names, as on some Fuji bicycles). Some, like 3Rensho and Nagasawa had/have a very high profile and their frames are sought after. But a particularly notable user of Ishiwata outside of the Japanese manufacturers was Trek.

In Trek's early years (mid 70s through early 80s, that is), they made bikes using Ishiwata, Reynolds, and Columbus. According to the Vintage Trek website and from the Trek brochures of the time, the frames were essentially the same -- certainly equal in quality -- only the tubing was different (and the Ishiwata-tubed models used SunTour dropouts as opposed to Campagnolo pieces -- but like the tubing, there was really no difference in quality). In those early years, the model numbers would indicate which tubing was used (5xx - Ishiwata 022; 7xx - Reynolds 531; 9xx - Columbus SL/SP). Mainly because of the dollar/yen exchange rate and other market-driven factors, the Ishiwata-tubed models were significantly less expensive than the others, which probably (unfairly) gave buyers the idea that they were somehow inferior. They weren't. Today, in the vintage bike marketplace, they can be a good value. In any case, by some time in the 80s, the Ishiwata tubing was dropped by Trek.

Ishiwata ended up going bankrupt in 1993, but some of their employees went on to found Kaisei which is being used by a number of steel-frame bicycle builders today. It has a well-earned reputation for quality.

Although it took time for Tange and Ishiwata to fully gain acceptance outside of Japan, especially for top-level bikes, there is no doubt that their quality was the equal of the European standards. Even though Japanese-built bikes, especially by the early to mid 80s, were (and still are) considered to be exceptionally well-crafted, especially for their price, for a while many fashion-conscious buyers of high-end, top-level bikes still looked for Reynolds or Columbus in their frames. The Trek example mentioned above is a pretty good illustration of that. But in today's vintage bike market, those bikes represent a real value -- super bargains. And the marketplace for new steel frames today doesn't really seem to discriminate the way it once did. Maybe it's because in a world of carbon fiber and welded aluminum bicycle madness, anyone buying a new steel frame is already bucking "fashion" enough that the brand or nationality on a little tubing sticker (assuming there even is one) just doesn't matter.

Although it took time for Tange and Ishiwata to fully gain acceptance outside of Japan, especially for top-level bikes, there is no doubt that their quality was the equal of the European standards. Even though Japanese-built bikes, especially by the early to mid 80s, were (and still are) considered to be exceptionally well-crafted, especially for their price, for a while many fashion-conscious buyers of high-end, top-level bikes still looked for Reynolds or Columbus in their frames. The Trek example mentioned above is a pretty good illustration of that. But in today's vintage bike market, those bikes represent a real value -- super bargains. And the marketplace for new steel frames today doesn't really seem to discriminate the way it once did. Maybe it's because in a world of carbon fiber and welded aluminum bicycle madness, anyone buying a new steel frame is already bucking "fashion" enough that the brand or nationality on a little tubing sticker (assuming there even is one) just doesn't matter.