In evolutionary biology, small mutations -- genetic "accidents" if you will -- occur naturally and occasionally. Sometimes these mutations turn out to be beneficial and live on, perhaps to even become a new species eventually. Consider the first fish that had the ability to breathe air on land, eventually leading to amphibians. Sometimes these offshoots of an evolutionary line go extinct, only to become an interesting curiosity in the fossil record. One might think of our distant forebearers, the Neanderthals (Homo Neanderthalensis) -- not a direct ancestor exactly, but more like an evolutionary cousin, whom some anthropologists believe may have even co-existed with early Homo Sapiens, but eventually died off, becoming an evolutionary dead-end.

In looking at bicycle derailleurs over the past couple of articles (HERE, and HERE), I couldn't help but see a similar phenomenon -- evolutionary dead ends in the line of bicycle components.

In the mid-to-late-80s, Campagnolo was fighting for its life. In 1985, Shimano introduced a new click-shifting version of Dura-Ace and kicked off the indexing revolution. Suddenly, everyone wanted click-shift derailleurs. SunTour responded quickly (though some would argue not quickly enough), while Campagnolo apparently hoped indexed shifting was a fad that would go away, and their first attempts at competing with it just could not hold their own against the competition. Not only that, but mountain bikes were sweeping the market, dominated by Japanese component groups. Between 1985 and 1990, Campagnolo introduced C-Record, Chorus, Croce d'Aune, and Athena -- each with a different derailleur design. In addition, there were two versions released of their Syncro indexing shift levers, plus Centaur and Euclid mountain-bike groups. By 1991, virtually all of them were either completely redesigned, or phased out.

Campagnolo took a very different approach than the Japanese to indexing with their Syncro design in 1987. Whereas Shimano and SunTour designed full systems of interrelated parts -- shift levers, derailleurs, freewheels/cassettes, chains, and even cables (necessitating a complete drivetrain component upgrade, or better yet, just a whole new bike) -- Campagnolo, on the other hand, tried to make Syncro work with their existing derailleurs. It didn't work. The standard parallelogram with a single spring-loaded pivot (which essentially dated back to about 1950) did not track the cogs as closely as the dropped/slanted parallelogram architecture, had a wide "chain gap" on the smaller cogs, and required a fair amount of the overshift/back-off technique to make the shift. None of this translated to good success with indexing. Not only that, but the design and spacing of the cogs, plus the chain design, and the fine-tuning of cable tension, all contributed to making indexed shifting reliable. Campy just didn't have it.

The C-Record derailleur had a sleek, modern, aerodynamic design, but functionally shared the same traditional architecture of the Super Record. The only real addition was to include a spring-loaded top pivot (like Simplex) which was an improvement, but not enough to make it index like Dura-Ace, or even the much cheaper Shimano 600 (soon renamed Ultegra) or SunTour's Accushift models. Although an improvement, the C-Record's basic parallelogram structure was on the verge of extinction.

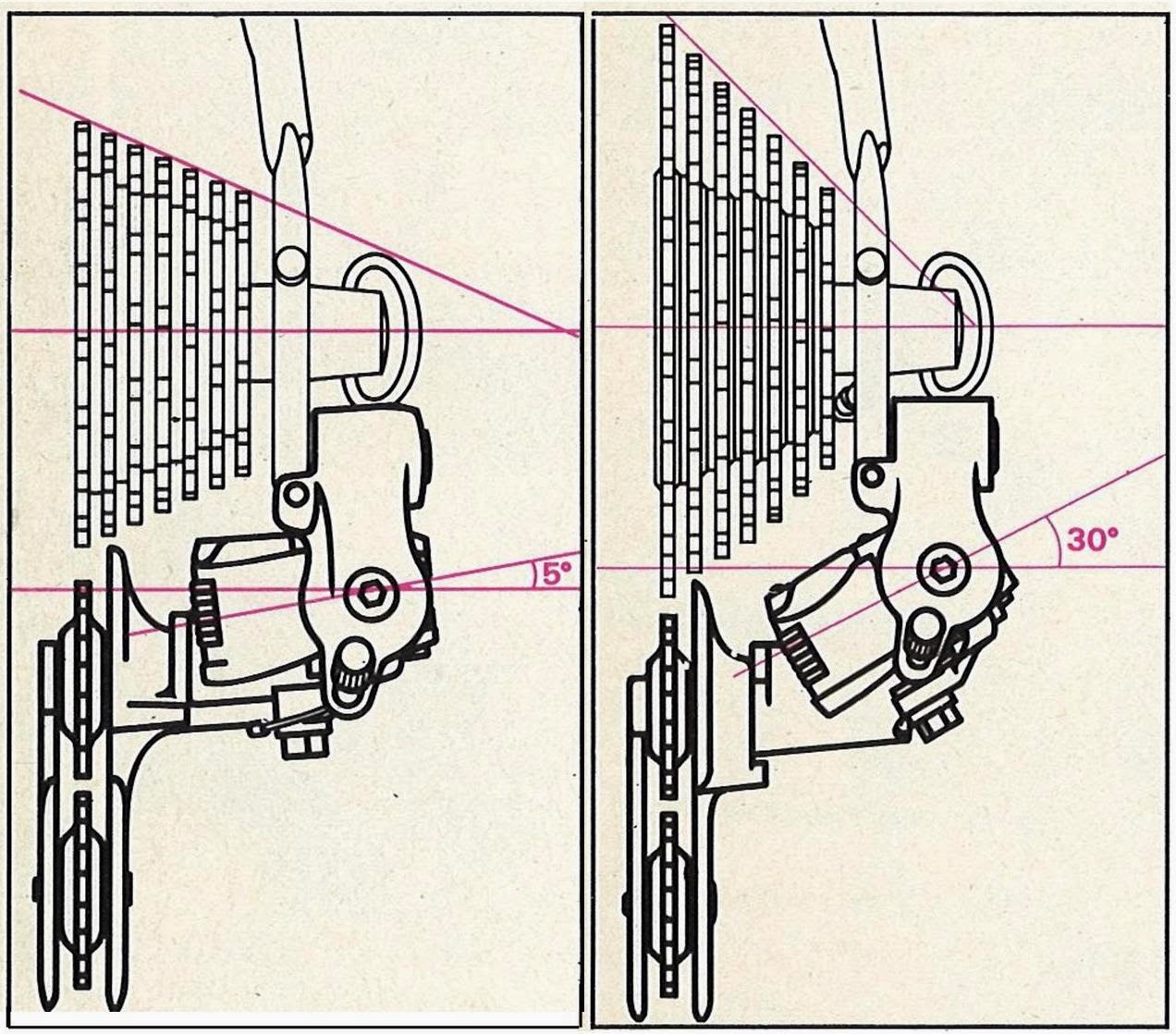

In 1987-88, Campagnolo released Chorus -- the first of their derailleurs to make a complete break with the traditional Campy design. It included a dropped, slanted parallelogram -- with a twist -- literally. Not content to just copy the Japanese design, Campagnolo designed the Chorus with a special 2-position parallelogram that could be tilted a little or a lot, depending on the range of the freewheel being used. A review of the group in Cyclist magazine, Feb. 1988, said, "We found Chorus worked better than any other Campy derailleur -- including the top-of-the-line C-Record. The Chorus derailleur shifted more precisely and was a lot quieter than past Campy derailleurs." They went on to say, "If you want indexed shifting on your all-Campy bike, Chorus plus Synchro is the best combination." As glowing as that review was, I don't believe that opinion was shared by all. The 2-position parallelogram was a really interesting idea -- but it never caught on. It would prove to be an evolutionary dead end.

In early 1988, Campagnolo released Croce d'Aune, named after the famous mountain pass where the young Tullio Campagnolo, his fingers frozen numb in the cold, was inspired to create the first quick release hub. The Croce d'Aune derailleur was a true oddity. Like the C-Record and almost all other Campy derailleurs dating back to the original Gran Sport, it utilized the traditional hanging parallelogram structure. Unlike any other, it used a combination of cable actuation and an unusual articulating tie-rod to keep it tracking the cogs closely with a narrower chain gap. Campy called it a "twin axle" system. According to Chuck Schmidt, of Velo-Retro, the top of the tie-rod was held by the derailleur fixing bolt with a ball joint, and the bottom of the rod moved with the derailleur body. Pulling the lever to shift, the cable pulled the body back, while the tie rod pushed the derailleur body inwards, driving it from one cog to the next. Again, the claim was that it would work better with indexed shifting -- but the market must have believed otherwise. The complicated and unusual structure never caught on and it was redesigned a few short years later. Another evolutionary dead-end.

In 1988-89, the Athena group was introduced, with yet another derailleur design. At first glance, the Athena appeared to share the traditional Campagnolo parallelogram structure. Not quite, though. If one looks a little closer, it becomes apparent that the parallelogram is actually canted at an angle. It looks like a traditional hanging parallelogram, but its angled movement would carry it downward as it moved inward towards the larger cogs, or upwards toward the smaller ones -- mimicking somewhat the movement of a slant parallelogram design. Another detail was that it had a small toothed "stop" at the upper pivot to set the angle of the derailleur as it hung from the dropout. It could be adjusted for different cog sizes. I've used the Athena, not with Campy's Synchro indexing shift levers, but rather with their excellent "retrofriction" levers (another nice bit of componentry that didn't survive the indexing era). With those smooth-acting levers, I've found that the Athena is a really nice shifting little derailleur. If it had been designed with a spring-loaded top pivot, instead of the little toothed stop, it might have been even better. The little adjustable toothed ring can break pretty easily, leaving the derailleur to pull forward without a stop until the pulley cage crashes into the cogs. It's happened to me, and I've seen others that have suffered the same fate (and good luck finding a replacement for the little ring!). Unfortunate, really. Again, it became another evolutionary dead-end.

The Syncro levers themselves also were redesigned in that 5-year timespan. The original levers, shown above, had an extra, smaller lever on the right side, that switched the unit from friction to indexing mode. In order to make it work with different derailleurs and cog sets, there were interchangeable inserts to control the number and spacing of the "clicks." There are people who love the system, and admittedly, it was admirable that Campy at least attempted to make it compatible with existing components, rather than necessitating a complete upgrade. But many found it pretty "finicky" to get set up properly. In 1989, there was a Syncro II, with even more insert rings for more compatibility with different drivetrain options, including 8-speed. The second version is identifiable for its large, knurled ring on the right side, in place of the mini lever, to switch between friction and indexing. By '92, the switchable Syncro levers with interchangeable rings were replaced with a simpler index-only lever for 8-speeds, along with Ergo integrated brake/shift levers.

By 1991, Campagnolo decided that when it came to the Japanese competition, they were better off just copying them rather than trying to beat them at their own game. The line of derailleurs, with all its unique variations, was completely redesigned -- all across the board with dropped, slanted parallelograms, borrowing heavily from the designs being used by Shimano. In addition, they came up with specially shaped cog teeth, not unlike Shimano's Hyperglide, all to finally get indexed shifting systems that worked the way the consumers seemed to be demanding.

Looking at the parts shown above, it's pretty clear Campagnolo in those years was doing anything they could to remain not only competitive, but innovative. Not content to just copy the Shimano and SunTour designs, they tried to remain true to their heritage and make their traditional designs work in the new era. The Chorus, Croce d'Aune, and Athena, all had very different approaches to improve shifting performance, but ultimately none of the innovations would last. Sadly (to my Retrogrouch sensibility, anyhow) the way Campagnolo regained its reputation as an innovator was to start squeezing extra cogs onto the cassette -- jumping ahead of Shimano first with 10, then 11 cogs. Now that Shimano is making their own 11 speed cassettes, what else is there to do for "innovation" but to try for 12?

Something to think about: The original Gran Sport was made with few changes for about 13 years or so. The Nuovo Record was made for even longer. The basic architecture of those derailleurs was used for roughly 40 years! Today, new components are introduced almost every year, with incremental changes billed as major design revolutions. The way the bicycle industry seems intent on making our bikes "obsolete" almost as soon as we ride them, it appears that their current slogan might be "mutate or die"!

In looking at bicycle derailleurs over the past couple of articles (HERE, and HERE), I couldn't help but see a similar phenomenon -- evolutionary dead ends in the line of bicycle components.

In the mid-to-late-80s, Campagnolo was fighting for its life. In 1985, Shimano introduced a new click-shifting version of Dura-Ace and kicked off the indexing revolution. Suddenly, everyone wanted click-shift derailleurs. SunTour responded quickly (though some would argue not quickly enough), while Campagnolo apparently hoped indexed shifting was a fad that would go away, and their first attempts at competing with it just could not hold their own against the competition. Not only that, but mountain bikes were sweeping the market, dominated by Japanese component groups. Between 1985 and 1990, Campagnolo introduced C-Record, Chorus, Croce d'Aune, and Athena -- each with a different derailleur design. In addition, there were two versions released of their Syncro indexing shift levers, plus Centaur and Euclid mountain-bike groups. By 1991, virtually all of them were either completely redesigned, or phased out.

|

| Version one of the Syncro levers. Note the extra lever on the right, which switched from indexing to friction shifting modes. |

Campagnolo took a very different approach than the Japanese to indexing with their Syncro design in 1987. Whereas Shimano and SunTour designed full systems of interrelated parts -- shift levers, derailleurs, freewheels/cassettes, chains, and even cables (necessitating a complete drivetrain component upgrade, or better yet, just a whole new bike) -- Campagnolo, on the other hand, tried to make Syncro work with their existing derailleurs. It didn't work. The standard parallelogram with a single spring-loaded pivot (which essentially dated back to about 1950) did not track the cogs as closely as the dropped/slanted parallelogram architecture, had a wide "chain gap" on the smaller cogs, and required a fair amount of the overshift/back-off technique to make the shift. None of this translated to good success with indexing. Not only that, but the design and spacing of the cogs, plus the chain design, and the fine-tuning of cable tension, all contributed to making indexed shifting reliable. Campy just didn't have it.

The C-Record derailleur had a sleek, modern, aerodynamic design, but functionally shared the same traditional architecture of the Super Record. The only real addition was to include a spring-loaded top pivot (like Simplex) which was an improvement, but not enough to make it index like Dura-Ace, or even the much cheaper Shimano 600 (soon renamed Ultegra) or SunTour's Accushift models. Although an improvement, the C-Record's basic parallelogram structure was on the verge of extinction.

|

| Diagram from a 1988 Chorus advertisement. |

|

| With its tie-rod actuation, the Croce d'Aune worked like no other derailleur before or since. |

| The original Athena looked like a traditional Campy-style derailleur, but the parallelogram was actually canted for better tracking down the profile of the cogs. |

|

| This little toothed ring on the mounting bolt allowed one to adjust for different sprockets. |

By 1991, Campagnolo decided that when it came to the Japanese competition, they were better off just copying them rather than trying to beat them at their own game. The line of derailleurs, with all its unique variations, was completely redesigned -- all across the board with dropped, slanted parallelograms, borrowing heavily from the designs being used by Shimano. In addition, they came up with specially shaped cog teeth, not unlike Shimano's Hyperglide, all to finally get indexed shifting systems that worked the way the consumers seemed to be demanding.

Looking at the parts shown above, it's pretty clear Campagnolo in those years was doing anything they could to remain not only competitive, but innovative. Not content to just copy the Shimano and SunTour designs, they tried to remain true to their heritage and make their traditional designs work in the new era. The Chorus, Croce d'Aune, and Athena, all had very different approaches to improve shifting performance, but ultimately none of the innovations would last. Sadly (to my Retrogrouch sensibility, anyhow) the way Campagnolo regained its reputation as an innovator was to start squeezing extra cogs onto the cassette -- jumping ahead of Shimano first with 10, then 11 cogs. Now that Shimano is making their own 11 speed cassettes, what else is there to do for "innovation" but to try for 12?

Something to think about: The original Gran Sport was made with few changes for about 13 years or so. The Nuovo Record was made for even longer. The basic architecture of those derailleurs was used for roughly 40 years! Today, new components are introduced almost every year, with incremental changes billed as major design revolutions. The way the bicycle industry seems intent on making our bikes "obsolete" almost as soon as we ride them, it appears that their current slogan might be "mutate or die"!