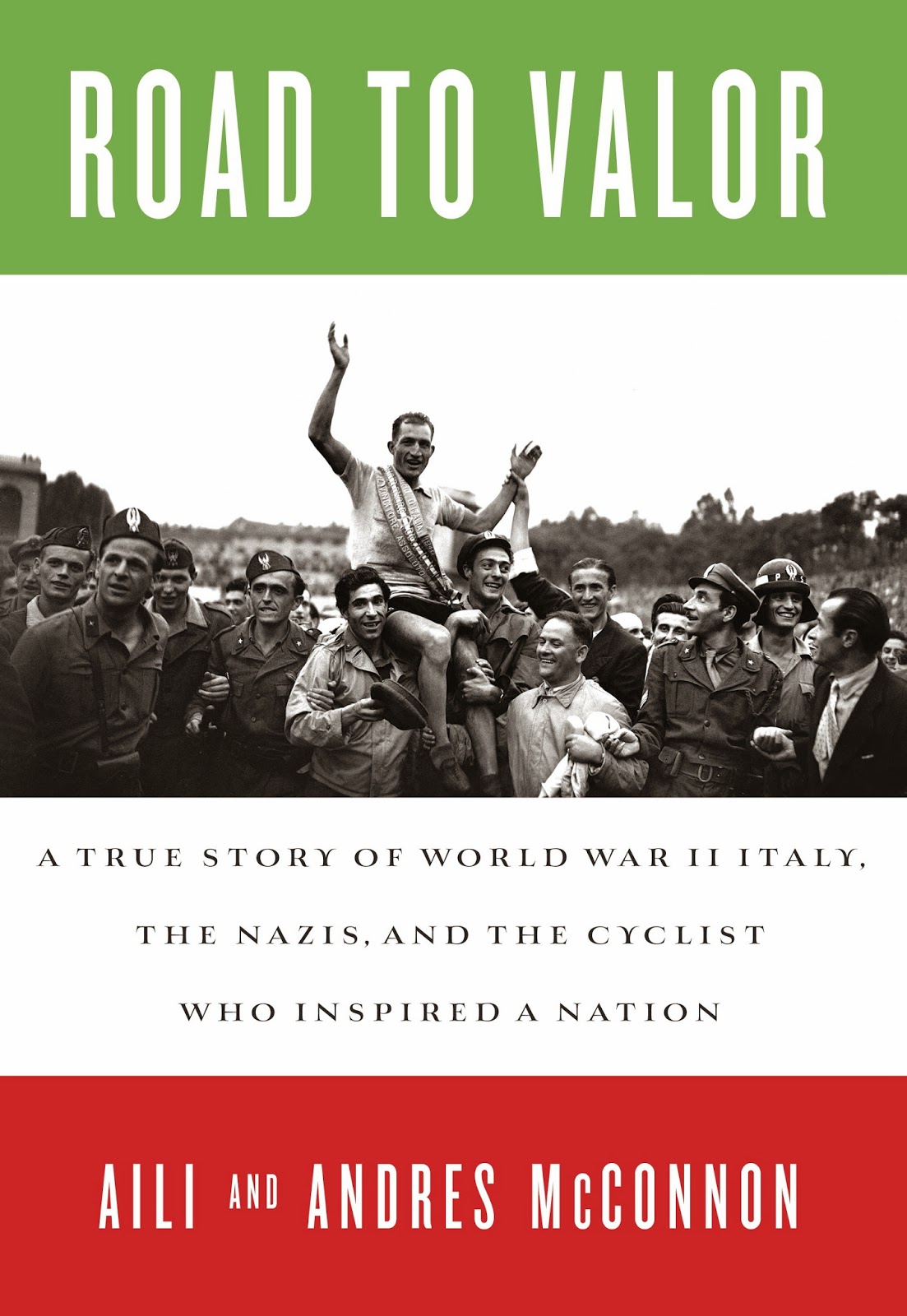

Many long-time fans of bicycle racing likely know the name of Gino Bartali, the Italian cycling legend of the 1930s and 40s. Many might be familiar with his two Tour de France victories, or his three wins in the Giro d'Italia. Some might even know of the great rivalry between Bartali and another great Italian, Fausto Coppi -- a rivalry that divided that nation's cycling fans for decades to come. But the book Road to Valor by Aili and Andres McConnon (2012 Crown Publishers) reveals that Bartali was not only a hero of cycling, but was also a hero of World War II -- particularly for his role with the Italian resistance to the Nazis and Fascists, and with the underground efforts to protect that country's Jews from the Holocaust.

Road to Valor: A True Story of World War II Italy, The Nazis, And the Cyclist Who Inspired a Nation, is a painstakingly researched and footnoted historical documentation of Bartali's previously unheralded role during the war, intertwined with the details of some of his most notable racing victories.

Although not a particularly political person, politics very much impacted Bartali's life and cycling career. The book describes how the fascist government under Mussolini took a great deal of control over the athletic governing bodies in Italy and used them for propaganda purposes. This put Bartali in a difficult position, being that his loyalties lay not with the Fascists, but with the group Catholic Action which was often at odds with the ruling party.

"Living in this world of Fascist sport, Gino began to find that the decision makers who surrounded him were increasingly driven by political motives. Athletic governing bodies, like the Italian Cycling Federation. . . were often staffed by high-ranking Fascist party members; the members of the press covering a sport answered to the regime, not to the readers or racers. A star athlete like Gino who didn't share all of the regime's ideological positions thus found himself in an unenviable position."At times, in those pre-war years, interference by politically motivated officials affected Bartali's appearances and performances in races -- and was at least a factor in denying Bartali his goal of winning both the Giro d'Italia and Tour de France in the same year.

One of the things readers will take from the book is how politics, and then World War II, essentially robbed Bartali of what should have been the best years of his racing career. Having won the Tour de France in 1938, while still in his 20s, he was denied the opportunity to defend his title the following year because of increasing tensions with France and the impending war. Professional bike racing ground to a halt during the war years. By the time the war was over and races like the Giro and the Tour were able to resume, many of the great pre-war racers were either dead, or shadows of their former selves.

But those details of Bartali's career are widely known. The most impressive chapters of Road to Valor describe Bartali's actions during those "lost" years of the war. Initially inducted into the military, Bartali was able to continue riding his bicycle as a messenger for the army. After Italy's initial surrender to the Allies in 1943, much of the country was taken over by the Nazis who kept Mussolini in charge as a puppet dictator. Unlike some soldiers at the time, Bartali was apparently not pressed again into service for the puppet regime. Meanwhile, the Fascists and the Nazis stepped up their efforts to round up Italy's population of Jewish citizens, much as they had done in other conquered territories. It was during this time that Bartali was enlisted by his trusted friend and advisor, Cardinal Elia Dalla Costa, to help with the effort to shelter those now-hunted citizens from persecution.

In what came to be known as the Assisi Underground, Gino Bartali was part of a network of people working to hide Italian Jews -- either by smuggling them out of the country, or by providing them with new identity documents to conceal their Jewish identity. Pretending to be in training (for races that were long since cancelled), Bartali rode his bicycle all over Fascist-controlled territory, delivering documents and photos for new identification (typically hidden in the tubes of his bicycle), and providing intelligence on raids and safe houses for the resistance. Considering that anyone caught as part of the effort to protect the Jewish citizens could be executed immediately, or tortured, or sent to concentration camps, it was a tremendous personal risk.

Not only that, but Road to Valor also documents the story of the Goldenberg family, who were personally sheltered by Bartali in an apartment that he paid for with his pre-war race earnings. One of the sources for the book was Giacomo Goldenberg, who was a young boy during the war and who still lives today in Israel. It's a very compelling story. Though there are no exact figures on exactly how many Jewish citizens in Italy were saved by the efforts of Bartali and the Assisi Underground (there being few if any official records remaining), the numbers are estimated to be over 300. Combined with the efforts of other groups working in other parts of Italy, the numbers of those saved are thought to be 600 - 800 people who would otherwise have perished in the concentration camps.

Following the war, Italy's troubles were not over, as a new political struggle replaced the old. Who would lead the newly liberated country? Christian Democrats, aligned with the Catholic Church and the USA, were in a power struggle with the Communists. It was one of the first battlegrounds of what would become the Cold War. While the Christian Democrats eventually won control, tensions continued. And again, Road to Valor documents how Bartali played an important role.

In 1948, ten years after his first Tour de France win, Bartali was finally given his chance to defend his win. Now in his 30s, being called "Il Vecchio," or "The Old Man," in the press, Bartali's chances of victory were hardly ensured. In the first weeks of the Tour, Bartali seemed to falter. "While I felt really good, everyone was going around saying that I was a finished man: an old man who still knew how to defend himself but that it took more than that to win the Tour," he recalled.

As the race went on in France, back at home in Italy, an assassination attempt on the Communist opposition leader sparked protests and demonstrations in cities all over the country. Some believed the country was in danger of being torn apart. At the height of tensions, the recently elected Italian Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi, a fan and acquaintance of Bartali's, called the racer at his hotel in France to ask about his chances of victory in the Tour. As Gino assured the Prime Minister, "I'm ninety percent sure I'll win tomorrow," (referring to the next day's stage), De Gasperi reportedly responded, "Try to make it happen. You know that it would be very important for all of us."

Gino Bartali made good on his promise, winning a brutally cold and muddy mountain stage and taking back most of his time deficit against the race leader. In the next stage, he repeated his performance, taking the race leader's yellow jersey and holding on to it all the way to Paris. In Italy, the news of Bartali's race comeback victory, along with news of the Communist leader's improved medical condition, defused the tensions that had threatened a revolt. Some called Gino Bartali "the 'savior of the Fatherland' who singlehandedly stopped the outbreak of a civil war." Others offered a somewhat more tempered assessment. "'To say that civil war was averted by a Tour de France victory is surely excessive,' but it was 'undeniable' . . . that Gino 'contributed to ease the tensions.'"

The book ends the debate on the subject with Bartali's own humble words. "For his part, Gino steadfastly downplayed his accomplishment, saying, 'I don't know if I saved the country, but I gave it back its smile.'"

Overall, the thing that makes this book so important is the fact that it is probably the most comprehensive, most thoroughly researched account of Gino Bartali's role during the war yet written. Much of the information about Bartali's actions in the resistance during the war was not widely known by the public until the publication of Road to Valor. Bartali himself barely mentioned his role and was reluctant to talk about it -- apparently due to the fact that he didn't want his fame to overshadow the work of others whom he believed to be just as crucial to the effort. But it is an incredibly compelling story -- not just for fans of cycling, but for anyone interested in a story of real heroism.

Bartali's two Tour de France victories, separated by ten years, are an achievement still unmatched today. But as Road to Valor makes clear, the real greatness of Gino Bartali may not have anything to do with bike racing, but rather for his heroic role in saving hundreds of people from one of the 20th Century's worst atrocities.

Road to Valor: A True Story of World War II Italy, The Nazis, And the Cyclist Who Inspired a Nation, is a painstakingly researched and footnoted historical documentation of Bartali's previously unheralded role during the war, intertwined with the details of some of his most notable racing victories.

Although not a particularly political person, politics very much impacted Bartali's life and cycling career. The book describes how the fascist government under Mussolini took a great deal of control over the athletic governing bodies in Italy and used them for propaganda purposes. This put Bartali in a difficult position, being that his loyalties lay not with the Fascists, but with the group Catholic Action which was often at odds with the ruling party.

"Living in this world of Fascist sport, Gino began to find that the decision makers who surrounded him were increasingly driven by political motives. Athletic governing bodies, like the Italian Cycling Federation. . . were often staffed by high-ranking Fascist party members; the members of the press covering a sport answered to the regime, not to the readers or racers. A star athlete like Gino who didn't share all of the regime's ideological positions thus found himself in an unenviable position."At times, in those pre-war years, interference by politically motivated officials affected Bartali's appearances and performances in races -- and was at least a factor in denying Bartali his goal of winning both the Giro d'Italia and Tour de France in the same year.

|

| Gino Bartali, young and dashing in 1936. |

But those details of Bartali's career are widely known. The most impressive chapters of Road to Valor describe Bartali's actions during those "lost" years of the war. Initially inducted into the military, Bartali was able to continue riding his bicycle as a messenger for the army. After Italy's initial surrender to the Allies in 1943, much of the country was taken over by the Nazis who kept Mussolini in charge as a puppet dictator. Unlike some soldiers at the time, Bartali was apparently not pressed again into service for the puppet regime. Meanwhile, the Fascists and the Nazis stepped up their efforts to round up Italy's population of Jewish citizens, much as they had done in other conquered territories. It was during this time that Bartali was enlisted by his trusted friend and advisor, Cardinal Elia Dalla Costa, to help with the effort to shelter those now-hunted citizens from persecution.

In what came to be known as the Assisi Underground, Gino Bartali was part of a network of people working to hide Italian Jews -- either by smuggling them out of the country, or by providing them with new identity documents to conceal their Jewish identity. Pretending to be in training (for races that were long since cancelled), Bartali rode his bicycle all over Fascist-controlled territory, delivering documents and photos for new identification (typically hidden in the tubes of his bicycle), and providing intelligence on raids and safe houses for the resistance. Considering that anyone caught as part of the effort to protect the Jewish citizens could be executed immediately, or tortured, or sent to concentration camps, it was a tremendous personal risk.

Not only that, but Road to Valor also documents the story of the Goldenberg family, who were personally sheltered by Bartali in an apartment that he paid for with his pre-war race earnings. One of the sources for the book was Giacomo Goldenberg, who was a young boy during the war and who still lives today in Israel. It's a very compelling story. Though there are no exact figures on exactly how many Jewish citizens in Italy were saved by the efforts of Bartali and the Assisi Underground (there being few if any official records remaining), the numbers are estimated to be over 300. Combined with the efforts of other groups working in other parts of Italy, the numbers of those saved are thought to be 600 - 800 people who would otherwise have perished in the concentration camps.

Following the war, Italy's troubles were not over, as a new political struggle replaced the old. Who would lead the newly liberated country? Christian Democrats, aligned with the Catholic Church and the USA, were in a power struggle with the Communists. It was one of the first battlegrounds of what would become the Cold War. While the Christian Democrats eventually won control, tensions continued. And again, Road to Valor documents how Bartali played an important role.

In 1948, ten years after his first Tour de France win, Bartali was finally given his chance to defend his win. Now in his 30s, being called "Il Vecchio," or "The Old Man," in the press, Bartali's chances of victory were hardly ensured. In the first weeks of the Tour, Bartali seemed to falter. "While I felt really good, everyone was going around saying that I was a finished man: an old man who still knew how to defend himself but that it took more than that to win the Tour," he recalled.

As the race went on in France, back at home in Italy, an assassination attempt on the Communist opposition leader sparked protests and demonstrations in cities all over the country. Some believed the country was in danger of being torn apart. At the height of tensions, the recently elected Italian Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi, a fan and acquaintance of Bartali's, called the racer at his hotel in France to ask about his chances of victory in the Tour. As Gino assured the Prime Minister, "I'm ninety percent sure I'll win tomorrow," (referring to the next day's stage), De Gasperi reportedly responded, "Try to make it happen. You know that it would be very important for all of us."

|

| Bartali's victory lap after the '48 Tour. |

The book ends the debate on the subject with Bartali's own humble words. "For his part, Gino steadfastly downplayed his accomplishment, saying, 'I don't know if I saved the country, but I gave it back its smile.'"

Overall, the thing that makes this book so important is the fact that it is probably the most comprehensive, most thoroughly researched account of Gino Bartali's role during the war yet written. Much of the information about Bartali's actions in the resistance during the war was not widely known by the public until the publication of Road to Valor. Bartali himself barely mentioned his role and was reluctant to talk about it -- apparently due to the fact that he didn't want his fame to overshadow the work of others whom he believed to be just as crucial to the effort. But it is an incredibly compelling story -- not just for fans of cycling, but for anyone interested in a story of real heroism.

Bartali's two Tour de France victories, separated by ten years, are an achievement still unmatched today. But as Road to Valor makes clear, the real greatness of Gino Bartali may not have anything to do with bike racing, but rather for his heroic role in saving hundreds of people from one of the 20th Century's worst atrocities.