I've been reading that bicycles have outsold cars for the last few years in the U.S. and in many other countries long dominated by cars. Even during recent downturns when bicycles sales have fallen, apparently the sales of cars in those years have fallen more, keeping the bicycle ahead. Many people would probably be surprised by that news, but it gets me thinking about another time when bicycle sales outstripped cars in this country -- the American Bike Boom of the early 1970s.

The early 70s Bike Boom saw a huge bubble in which bicycle sales more than doubled practically overnight, only to see those gains almost completely erased when the boom went bust a few years later. Nevertheless, the Bike Boom marked a major shift in the American bicycle market, and sowed the seeds for huge changes in the manufacture and sales of bicycles and components around the world.

Though bike sales, like any commodity, saw their ups and downs, in general there was overall a long-term growth trend, with small, incremental increases from year to year. For example, U.S. bicycle sales totaled about 2 million in 1950, around 4 million in 1960, about 6 million in '65, and about 7 million in 1970. Suddenly, in 1971, sales shot to 9 million bicycles. In '72, the numbers went to nearly 14 million. 1973 was the peak, with more than 15 million bicycles sold. The number fell back slightly to 14 million in '74. The bubble burst in 1975, with sales dropping back to their pre-boom level of 7 million. (AAA Report)

|

| Sales chart from a 1978 AAA report. |

A lot of people mistakenly believe the Boom was caused by the oil embargo and the resulting shortages at the fuel pumps -- but the OPEC oil embargo didn't hit until the end of '73, and as the numbers above show, the Boom was well under way before that happened. So then, why did Americans suddenly start buying bicycles in ever greater numbers?

One of the better accounts I've read about the American Bike Boom was an article by Frank Berto that appeared in the Spring 2000 issue of The Rivendell Reader, #19 (most of the info can also be found in his book, The Dancing Chain). Citing a study conducted by Schwinn in the later 70s, Berto concluded that one of the major factors leading to the Boom was the "High-Rise,""Muscle-Bike,""Wheelie Bike," or "Sting-Ray" (call them what you will) bike fad of the 1960s. That fad got a lot of kids riding bikes, and in many cases, kept them riding past the age when they would have normally traded in their bikes for a set of car keys. Now, I'm summarizing a bit and leaving out a lot of detail, but essentially the assertion is made that the same kids who were riding those Sting-Rays and other muscle-bikes went on to "graduate," if you will, to the "10-speeds" that practically came to define the notion of the Bike Boom bicycles. By the way, I think it's worth noting that a lot of those muscle-bikes (at least the higher-end and more desirable ones) were often multi-speed derailleur-equipped bikes -- so it would seem like a natural progression that the kids would want to move up to the fast and exotic-seeming (at the time) 10-speeds that were starting to hit the market in greater numbers.

Another thing that contributed to the Bicycle Boom was the economic condition at the time for that other Boom -- the Baby Boom generation. Simply through their massive numbers the Baby Boomers had the ability to make big waves with any fad or trend they jumped onto. As Boomers came of age, reaching their teens and young adulthood, they also happened to be financially more independent than previous generations at the same age, having more disposable income to spend on discretionary purchases. Bicycles turned out to be one of those things they wanted to spend that money on.

Many people also believe there was a bit of a "counterculture" element to the Bike Boom. The previous generations -- the "establishment," if you will, were very much about cars -- the ultimate American status symbol. The new, younger generation was ready to question the priorities. There was definitely a different consciousness, and more interest in the environment, and bicycles probably fit into that idealism. Don't forget that the first "Earth Day" happened in April of 1970. In all I've read about the Bike Boom, nobody ever seems to mention that specifically, but I don't think it's an unrelated coincidence that Baby Boomers were finding bicycles to be an exciting alternative in the next couple of years.

The Bike Boom re-shaped the American bicycle market tremendously. Up until that point, bicycles were primarily seen as "toys" for kids. Few people rode bikes once they got their drivers' licenses. The American market was heavily dominated by kids' bikes -- like the 16" and 20" wheeled bicycles for younger children (say, age 4 - 9), middleweight 24" wheeled bikes for those older kids (say, 9 - 12), and middleweight or heavyweight (determined mainly by tire width) 26" wheeled bikes for the young teens. The "lightweight" category, aimed at older teens and adults, was more or less defined back then by 26 - 27" wheels with tires less than 1-3/4" wide (multi-speeds, whether internal hub or derailleur-equipped, were often a feature of the category as well). Of all those various market segments, the lightweight category typically accounted for no more than 10% of sales prior to the Bike Boom.

According to a Schwinn study, in the 60s, with the muscle-bike fad, the 20" category grew tremendously, but mostly at the expense of the 24" segment which took a huge hit (the late Sheldon Brown described that development as regrettable, and the 24" market never really recovered). During the Boom, the lightweight category exploded, growing to 37% in 1971, and peaking at 73% in 1974. Even after the bust, lightweights would continue to account for anywhere from 40% to 50% of the market for years after the Boom ended.

Another way the bicycle market was forever changed was through a shift in the manufacturing centers for the industry. With the huge increase in American demand for bicycles, the industry struggled to keep up. The big, well-known bicycle brands, like Schwinn, Raleigh, Peugeot, and others were at full capacity. The established component manufacturers, centered mainly in Europe, were also at full capacity and unable to meet the demand. For some brands, (especially in the lower price ranges) quality suffered in the attempt to increase production. Some manufacturers, distributers, and other companies, in order to fill the gaps in supply, turned to new sources -- and Japanese companies were ready.

Schwinn is a good example of what changes happened, but the story was repeated to some extent with many of the established makers. With bicycle orders far exceeding their production capacity, Schwinn started importing bicycles from Japan, badged "Schwinn Approved," and built by either Bridgestone or National Mfg/Panasonic. The Chicago-built 10-speeds that were the big sellers of the time were the Varsity and the Continental. They had heavy "electro-forged" (i.e. flash welded) frames, one-piece steel "Ashtabula" cranks, and Huret Allvit derailleurs. The Continental sold for about $15 more than the Varsity, and for that extra charge, one got tubular-steel fork blades, as opposed to the Varsity's flat-looking forged fork. The Japanese-built Schwinn World Traveler had a lugged steel frame, and Shimano derailleurs. It was priced about the same or slightly below the Varsity, weighed less, and worked better. How this would affect the American giant in the long run is practically a cautionary tale. In the face of how the Japanese-built Schwinns stacked up against the American-built models, did Schwinn take steps to make their domestic models better? Nope. They continued making bikes like the Varsity with nothing more than color and decal changes right into the early 80s (I realize there were probably a number of reasons for that, but I don't think anyone can deny that complacency was one of them).

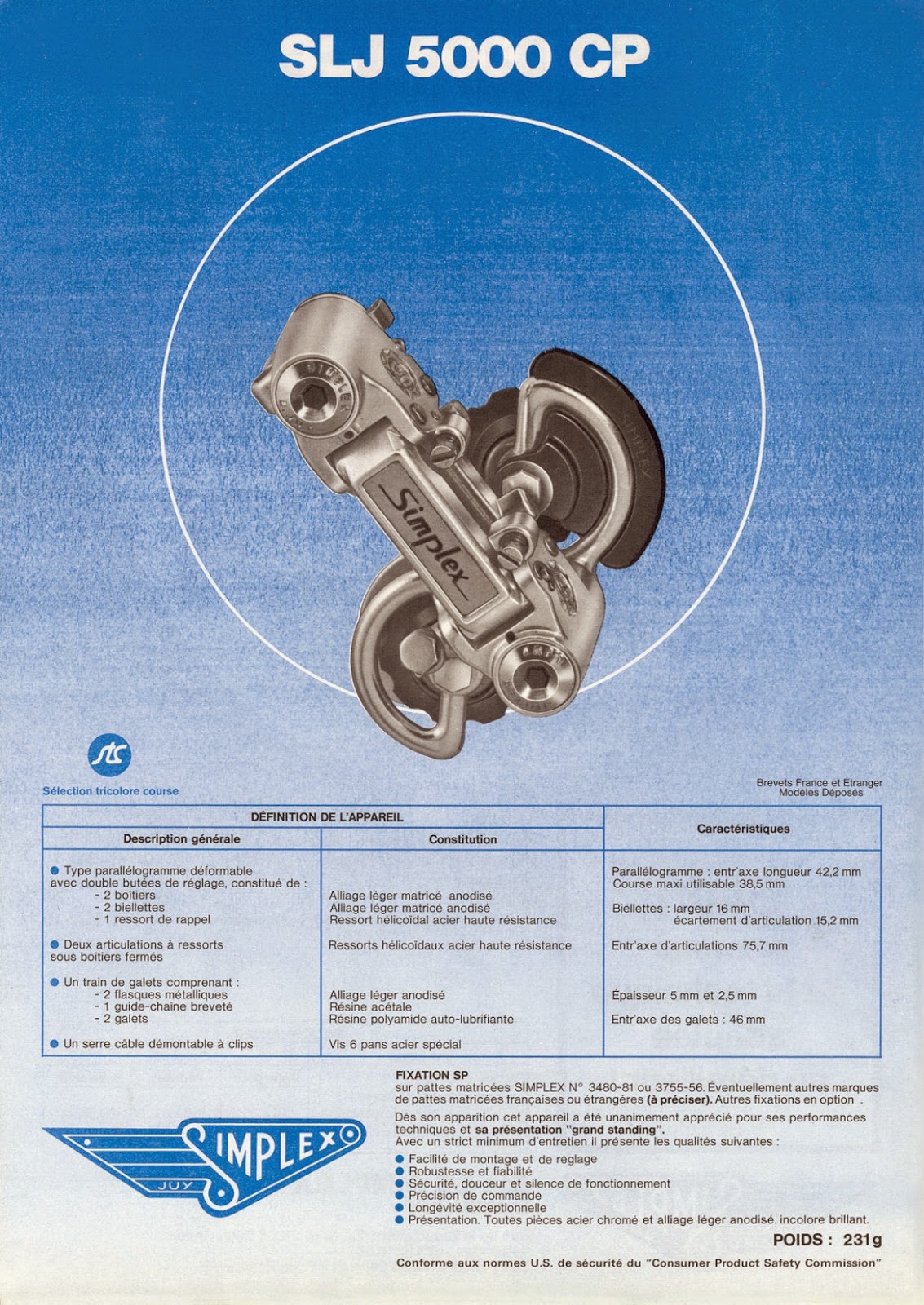

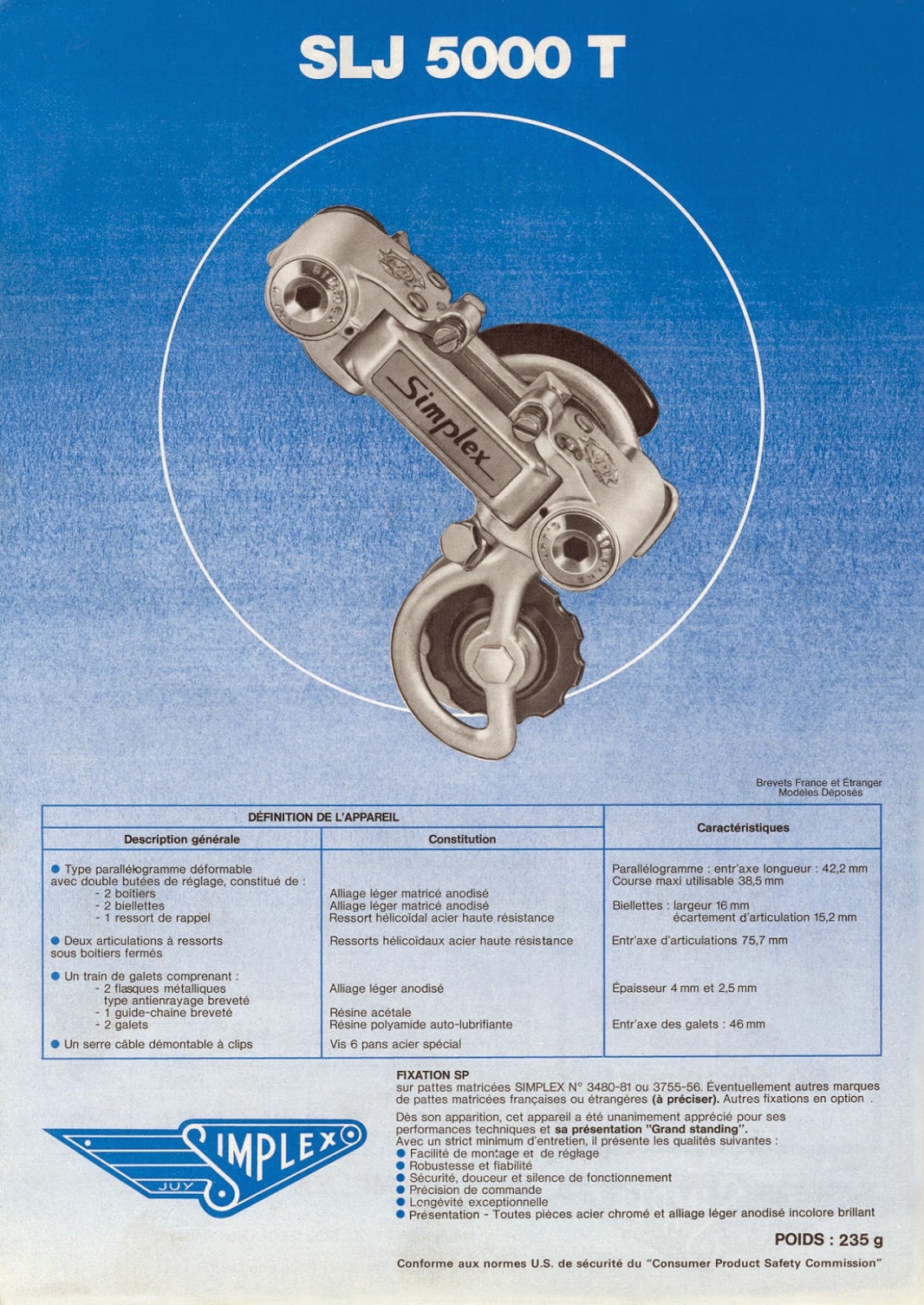

Likewise, as some of the major component makers from Europe, like Huret, Simplex, and others, were unable to meet the demand, companies like Sugino, Shimano and SunTour stepped up to fill the gaps, and often provided better components for the money. A Shimano Lark derailleur had a similar design to the Simplex Prestige, but was all steel (as opposed to the plastic "delrin" Simplex), much more durable, and shifted more reliably. A slant-parallelogram SunTour cost less than a Huret Allvit and shifted better than anything else at the time.

Bicycle manufactures, like Fuji, Nishiki, and others, found many buyers willing to give a Japanese brand a try -- and were pleased with what they got. On the whole, the American market was opened up to the Japanese brands, and they proved to be some of the best bargains of the era in the lower-to-mid priced levels (where the bulk of Bike Boom sales were) -- offering the best performance and reliability for the money. When the Boom went bust in '75, those companies that survived were well placed to increase their share, eventually dominating the European brands.

When sales skyrocketed at the start of the decade, all kinds of people jumped into the bicycle business, but it didn't last. In a way, it was just another fad, and even the long lines at the gas pumps in '74 didn't keep the sales going into the next year. People have short memories, I guess. It also hurt that the fuel shortages led to economic downturn and inflation, so things were tough all over. After gearing up for huge production in the previous couple of years, 1975 found bike manufacturers and shops sitting on tons of unsold inventory. Many of the startups fell on hard times, and many went under.

The effects of the bust were just as dramatic as the boom, but the whole cycle completely changed the bicycle market for years to come. America became a major market for adult-style multi-speed bikes. Japanese companies gained major inroads to the market, and supplanted the established European brands both for components and complete bicycles.

After the boom ended, bicycle sales in the U.S. went back to their gradual rising trend -- some years good, some years taking a downturn, but generally trending upwards. Sales figures climbed more steeply in the early 80s as mountain bikes became the next big thing, and eventually by the 90s the numbers reached, and even exceeded -- the same levels they had attained at the peak of the boom in the 70s.

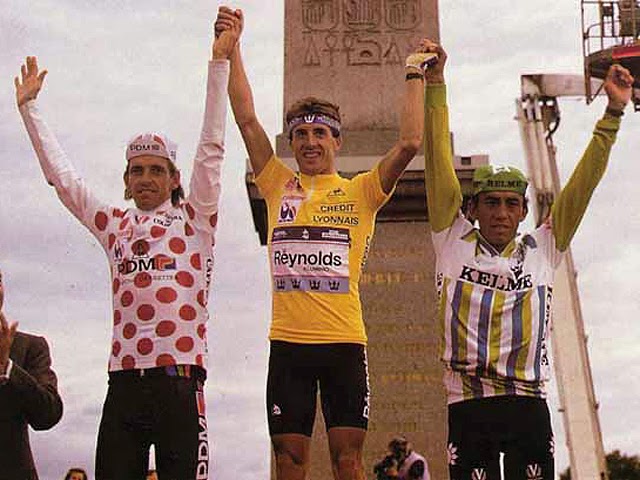

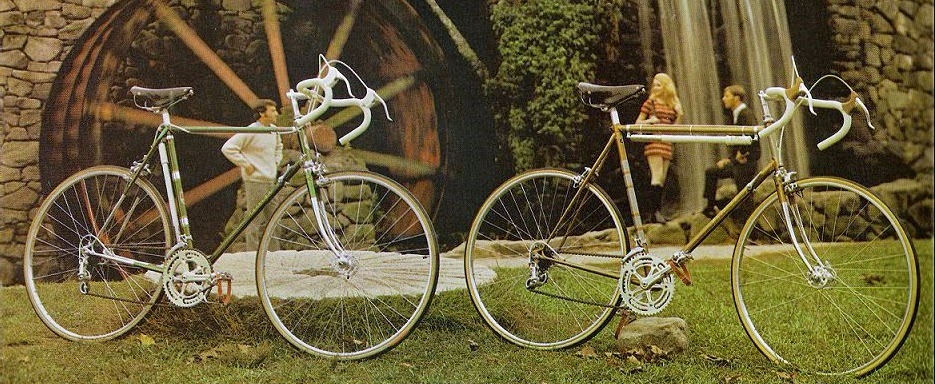

|

| Could this have helped kick off the Bike Boom? |

Another thing that contributed to the Bicycle Boom was the economic condition at the time for that other Boom -- the Baby Boom generation. Simply through their massive numbers the Baby Boomers had the ability to make big waves with any fad or trend they jumped onto. As Boomers came of age, reaching their teens and young adulthood, they also happened to be financially more independent than previous generations at the same age, having more disposable income to spend on discretionary purchases. Bicycles turned out to be one of those things they wanted to spend that money on.

Many people also believe there was a bit of a "counterculture" element to the Bike Boom. The previous generations -- the "establishment," if you will, were very much about cars -- the ultimate American status symbol. The new, younger generation was ready to question the priorities. There was definitely a different consciousness, and more interest in the environment, and bicycles probably fit into that idealism. Don't forget that the first "Earth Day" happened in April of 1970. In all I've read about the Bike Boom, nobody ever seems to mention that specifically, but I don't think it's an unrelated coincidence that Baby Boomers were finding bicycles to be an exciting alternative in the next couple of years.

The Bike Boom re-shaped the American bicycle market tremendously. Up until that point, bicycles were primarily seen as "toys" for kids. Few people rode bikes once they got their drivers' licenses. The American market was heavily dominated by kids' bikes -- like the 16" and 20" wheeled bicycles for younger children (say, age 4 - 9), middleweight 24" wheeled bikes for those older kids (say, 9 - 12), and middleweight or heavyweight (determined mainly by tire width) 26" wheeled bikes for the young teens. The "lightweight" category, aimed at older teens and adults, was more or less defined back then by 26 - 27" wheels with tires less than 1-3/4" wide (multi-speeds, whether internal hub or derailleur-equipped, were often a feature of the category as well). Of all those various market segments, the lightweight category typically accounted for no more than 10% of sales prior to the Bike Boom.

According to a Schwinn study, in the 60s, with the muscle-bike fad, the 20" category grew tremendously, but mostly at the expense of the 24" segment which took a huge hit (the late Sheldon Brown described that development as regrettable, and the 24" market never really recovered). During the Boom, the lightweight category exploded, growing to 37% in 1971, and peaking at 73% in 1974. Even after the bust, lightweights would continue to account for anywhere from 40% to 50% of the market for years after the Boom ended.

Another way the bicycle market was forever changed was through a shift in the manufacturing centers for the industry. With the huge increase in American demand for bicycles, the industry struggled to keep up. The big, well-known bicycle brands, like Schwinn, Raleigh, Peugeot, and others were at full capacity. The established component manufacturers, centered mainly in Europe, were also at full capacity and unable to meet the demand. For some brands, (especially in the lower price ranges) quality suffered in the attempt to increase production. Some manufacturers, distributers, and other companies, in order to fill the gaps in supply, turned to new sources -- and Japanese companies were ready.

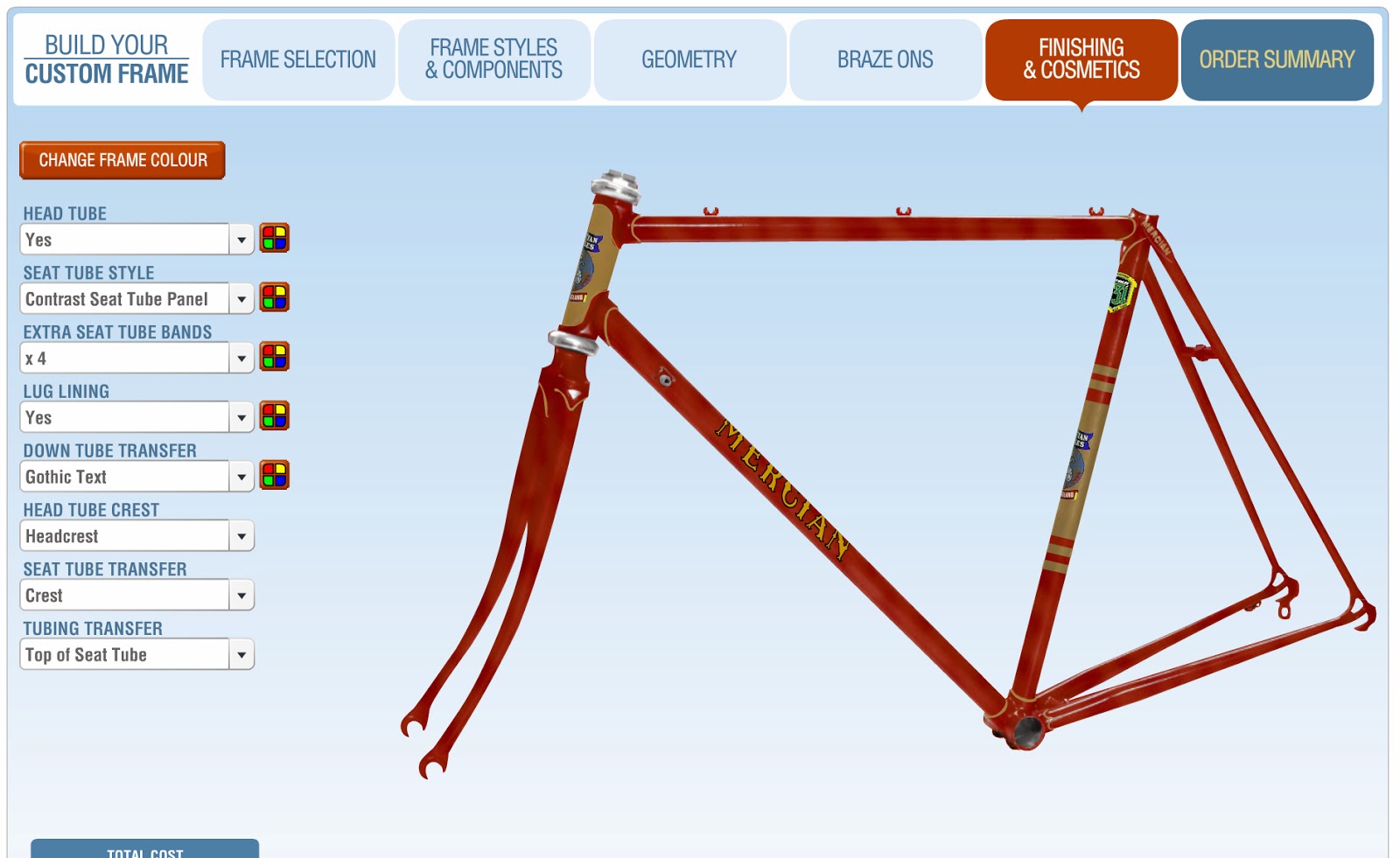

|

| The Schwinn Varsity was one of the best selling "10-speeds" of the Bike Boom era. |

Likewise, as some of the major component makers from Europe, like Huret, Simplex, and others, were unable to meet the demand, companies like Sugino, Shimano and SunTour stepped up to fill the gaps, and often provided better components for the money. A Shimano Lark derailleur had a similar design to the Simplex Prestige, but was all steel (as opposed to the plastic "delrin" Simplex), much more durable, and shifted more reliably. A slant-parallelogram SunTour cost less than a Huret Allvit and shifted better than anything else at the time.

Bicycle manufactures, like Fuji, Nishiki, and others, found many buyers willing to give a Japanese brand a try -- and were pleased with what they got. On the whole, the American market was opened up to the Japanese brands, and they proved to be some of the best bargains of the era in the lower-to-mid priced levels (where the bulk of Bike Boom sales were) -- offering the best performance and reliability for the money. When the Boom went bust in '75, those companies that survived were well placed to increase their share, eventually dominating the European brands.

When sales skyrocketed at the start of the decade, all kinds of people jumped into the bicycle business, but it didn't last. In a way, it was just another fad, and even the long lines at the gas pumps in '74 didn't keep the sales going into the next year. People have short memories, I guess. It also hurt that the fuel shortages led to economic downturn and inflation, so things were tough all over. After gearing up for huge production in the previous couple of years, 1975 found bike manufacturers and shops sitting on tons of unsold inventory. Many of the startups fell on hard times, and many went under.

The effects of the bust were just as dramatic as the boom, but the whole cycle completely changed the bicycle market for years to come. America became a major market for adult-style multi-speed bikes. Japanese companies gained major inroads to the market, and supplanted the established European brands both for components and complete bicycles.

After the boom ended, bicycle sales in the U.S. went back to their gradual rising trend -- some years good, some years taking a downturn, but generally trending upwards. Sales figures climbed more steeply in the early 80s as mountain bikes became the next big thing, and eventually by the 90s the numbers reached, and even exceeded -- the same levels they had attained at the peak of the boom in the 70s.

.gif)