The world has a new Hour Record holder. Yesterday in Switzerland Jens Voigt rode 51.115 km in one hour, beating the previous record of 49.700 km set by Ondrej Sosenka in 2005. Voigt is the first to pass the 50 km mark in the Hour Record since the UCI changed the rules earlier this year. I had written about the Hour Record back in May after the rule change which would allow more aerodynamic equipment to be used in record attempts. Since 2000, equipment was limited to what was available when Eddy Merckx broke the record in 1972, and any records set with disc wheels and other aerodynamic tricks were re-classified as "Best Human Effort."

![]() While I really liked the idea of keeping the record more "pure" by limiting the technology (to keep it a competition of men, not machines!), I also recognize the desire to simplify things by having just one "Hour Record" instead of having different categories with different rules. In any case, the rules now state that any bike approved for use in Individual Pursuit events can be used for the Hour Record. Still, I can't help but find myself wondering how would Eddy have done on a bike with special bars and disc wheels?

While I really liked the idea of keeping the record more "pure" by limiting the technology (to keep it a competition of men, not machines!), I also recognize the desire to simplify things by having just one "Hour Record" instead of having different categories with different rules. In any case, the rules now state that any bike approved for use in Individual Pursuit events can be used for the Hour Record. Still, I can't help but find myself wondering how would Eddy have done on a bike with special bars and disc wheels?

The bike Voigt used in his record ride was a Trek Speed Concept 9 Time Trial bike, modified for use on the track. Mainly, the modifications meant eliminating brakes and derailleurs, and building the frame with rear-facing track fork ends at the back. Surprisingly, the chainline and such was still the same as the road-going TT bike. The bike also had disc wheels front and rear (with a cool "stopwatch face" design on them).

![]() Some might recall that earlier in the year it had been Voigt's Trek teammate Fabian Cancellara who was contemplating an Hour Record attempt, but apparently reconsidered after the rules were changed. "The whole appeal of the Hour Record for me is that you are competing against riders from the past. I would have loved to race Eddy (Merckx) in the Classics, or in a time trial, but that's not possible," Cancellara had said. "The Hour Record has this charming side to it that I like a lot. Now it's going to be different." Though the rule change might have been the reason for changing his mind, some bloggers at the time suggested that it might have been Trek that wanted him to reconsider. But clearly Trek was able to get a suitable bike ready for the record attempt, so it now seems that that was an incorrect assessment. Now it really makes me wonder why Cancellara didn't make the attempt. Maybe he still will?

Some might recall that earlier in the year it had been Voigt's Trek teammate Fabian Cancellara who was contemplating an Hour Record attempt, but apparently reconsidered after the rules were changed. "The whole appeal of the Hour Record for me is that you are competing against riders from the past. I would have loved to race Eddy (Merckx) in the Classics, or in a time trial, but that's not possible," Cancellara had said. "The Hour Record has this charming side to it that I like a lot. Now it's going to be different." Though the rule change might have been the reason for changing his mind, some bloggers at the time suggested that it might have been Trek that wanted him to reconsider. But clearly Trek was able to get a suitable bike ready for the record attempt, so it now seems that that was an incorrect assessment. Now it really makes me wonder why Cancellara didn't make the attempt. Maybe he still will?

![]() Jens Voigt's Hour Record is a great achievement, and it caps the end of an impressive career in bicycle racing. Said Voigt, "I saw Chris Boardman beating the record in 2000 and I said to myself, 'what a great way that would be to finish my career.' Thirty three years of cycling behind me. This was my last attempt. I'm in so much pain . . . but what a way to retire!" One thing to add about Jens Voigt is that he will be missed in professional bike racing. In interviews with the press, he always seemed genuine and likable. Even when hammering on the road leading a mad-dash breakaway, he often managed a smile for the cameras and the fans. While nobody should doubt for a moment that bicycle racing is hard work, Voigt always managed to make it look fun.

Jens Voigt's Hour Record is a great achievement, and it caps the end of an impressive career in bicycle racing. Said Voigt, "I saw Chris Boardman beating the record in 2000 and I said to myself, 'what a great way that would be to finish my career.' Thirty three years of cycling behind me. This was my last attempt. I'm in so much pain . . . but what a way to retire!" One thing to add about Jens Voigt is that he will be missed in professional bike racing. In interviews with the press, he always seemed genuine and likable. Even when hammering on the road leading a mad-dash breakaway, he often managed a smile for the cameras and the fans. While nobody should doubt for a moment that bicycle racing is hard work, Voigt always managed to make it look fun.

While I really liked the idea of keeping the record more "pure" by limiting the technology (to keep it a competition of men, not machines!), I also recognize the desire to simplify things by having just one "Hour Record" instead of having different categories with different rules. In any case, the rules now state that any bike approved for use in Individual Pursuit events can be used for the Hour Record. Still, I can't help but find myself wondering how would Eddy have done on a bike with special bars and disc wheels?

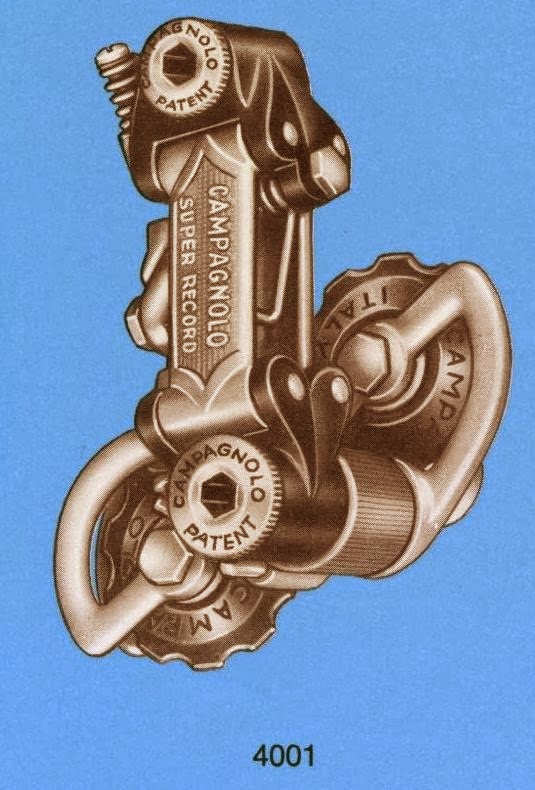

While I really liked the idea of keeping the record more "pure" by limiting the technology (to keep it a competition of men, not machines!), I also recognize the desire to simplify things by having just one "Hour Record" instead of having different categories with different rules. In any case, the rules now state that any bike approved for use in Individual Pursuit events can be used for the Hour Record. Still, I can't help but find myself wondering how would Eddy have done on a bike with special bars and disc wheels?The bike Voigt used in his record ride was a Trek Speed Concept 9 Time Trial bike, modified for use on the track. Mainly, the modifications meant eliminating brakes and derailleurs, and building the frame with rear-facing track fork ends at the back. Surprisingly, the chainline and such was still the same as the road-going TT bike. The bike also had disc wheels front and rear (with a cool "stopwatch face" design on them).

Some might recall that earlier in the year it had been Voigt's Trek teammate Fabian Cancellara who was contemplating an Hour Record attempt, but apparently reconsidered after the rules were changed. "The whole appeal of the Hour Record for me is that you are competing against riders from the past. I would have loved to race Eddy (Merckx) in the Classics, or in a time trial, but that's not possible," Cancellara had said. "The Hour Record has this charming side to it that I like a lot. Now it's going to be different." Though the rule change might have been the reason for changing his mind, some bloggers at the time suggested that it might have been Trek that wanted him to reconsider. But clearly Trek was able to get a suitable bike ready for the record attempt, so it now seems that that was an incorrect assessment. Now it really makes me wonder why Cancellara didn't make the attempt. Maybe he still will?

Some might recall that earlier in the year it had been Voigt's Trek teammate Fabian Cancellara who was contemplating an Hour Record attempt, but apparently reconsidered after the rules were changed. "The whole appeal of the Hour Record for me is that you are competing against riders from the past. I would have loved to race Eddy (Merckx) in the Classics, or in a time trial, but that's not possible," Cancellara had said. "The Hour Record has this charming side to it that I like a lot. Now it's going to be different." Though the rule change might have been the reason for changing his mind, some bloggers at the time suggested that it might have been Trek that wanted him to reconsider. But clearly Trek was able to get a suitable bike ready for the record attempt, so it now seems that that was an incorrect assessment. Now it really makes me wonder why Cancellara didn't make the attempt. Maybe he still will? Jens Voigt's Hour Record is a great achievement, and it caps the end of an impressive career in bicycle racing. Said Voigt, "I saw Chris Boardman beating the record in 2000 and I said to myself, 'what a great way that would be to finish my career.' Thirty three years of cycling behind me. This was my last attempt. I'm in so much pain . . . but what a way to retire!" One thing to add about Jens Voigt is that he will be missed in professional bike racing. In interviews with the press, he always seemed genuine and likable. Even when hammering on the road leading a mad-dash breakaway, he often managed a smile for the cameras and the fans. While nobody should doubt for a moment that bicycle racing is hard work, Voigt always managed to make it look fun.

Jens Voigt's Hour Record is a great achievement, and it caps the end of an impressive career in bicycle racing. Said Voigt, "I saw Chris Boardman beating the record in 2000 and I said to myself, 'what a great way that would be to finish my career.' Thirty three years of cycling behind me. This was my last attempt. I'm in so much pain . . . but what a way to retire!" One thing to add about Jens Voigt is that he will be missed in professional bike racing. In interviews with the press, he always seemed genuine and likable. Even when hammering on the road leading a mad-dash breakaway, he often managed a smile for the cameras and the fans. While nobody should doubt for a moment that bicycle racing is hard work, Voigt always managed to make it look fun. |

| A fitting farewell. |